Transforming freeways into high-performing multi-modal corridors:

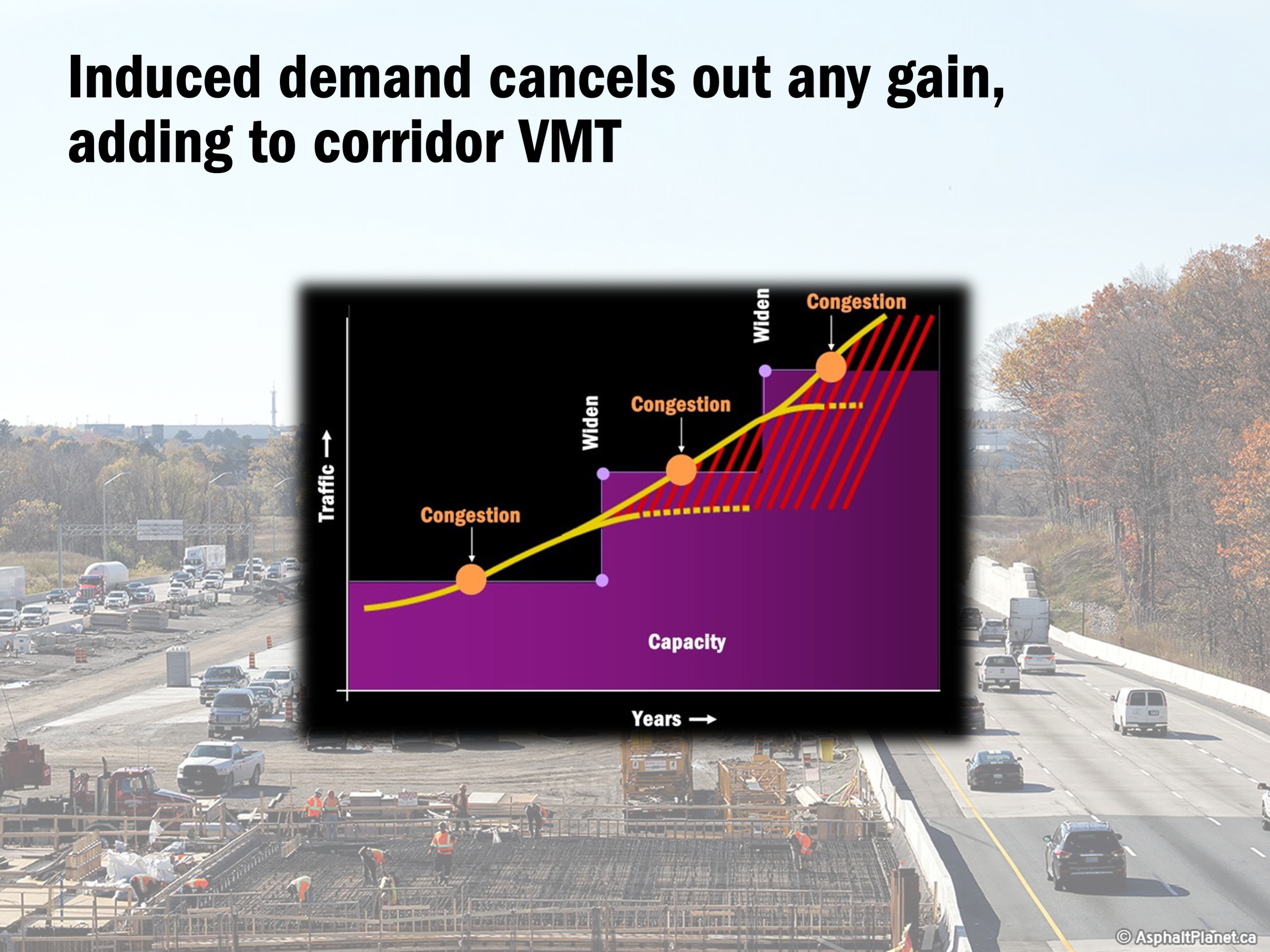

For decades, the default response to freeway congestion in the U.S. was to build more lanes. But this strategy has backfired, thanks to a well-documented phenomenon known as induced demand—where adding capacity only attracts more drivers, ultimately restoring or worsening congestion.

The Katy Freeway in Houston (pictured below), now 26 lanes wide, stands as a striking example. Despite multiple expansions aimed at relieving traffic, the corridor remains heavily congested. Each widening simply encouraged more development and more driving, creating a costly, unsustainable cycle.

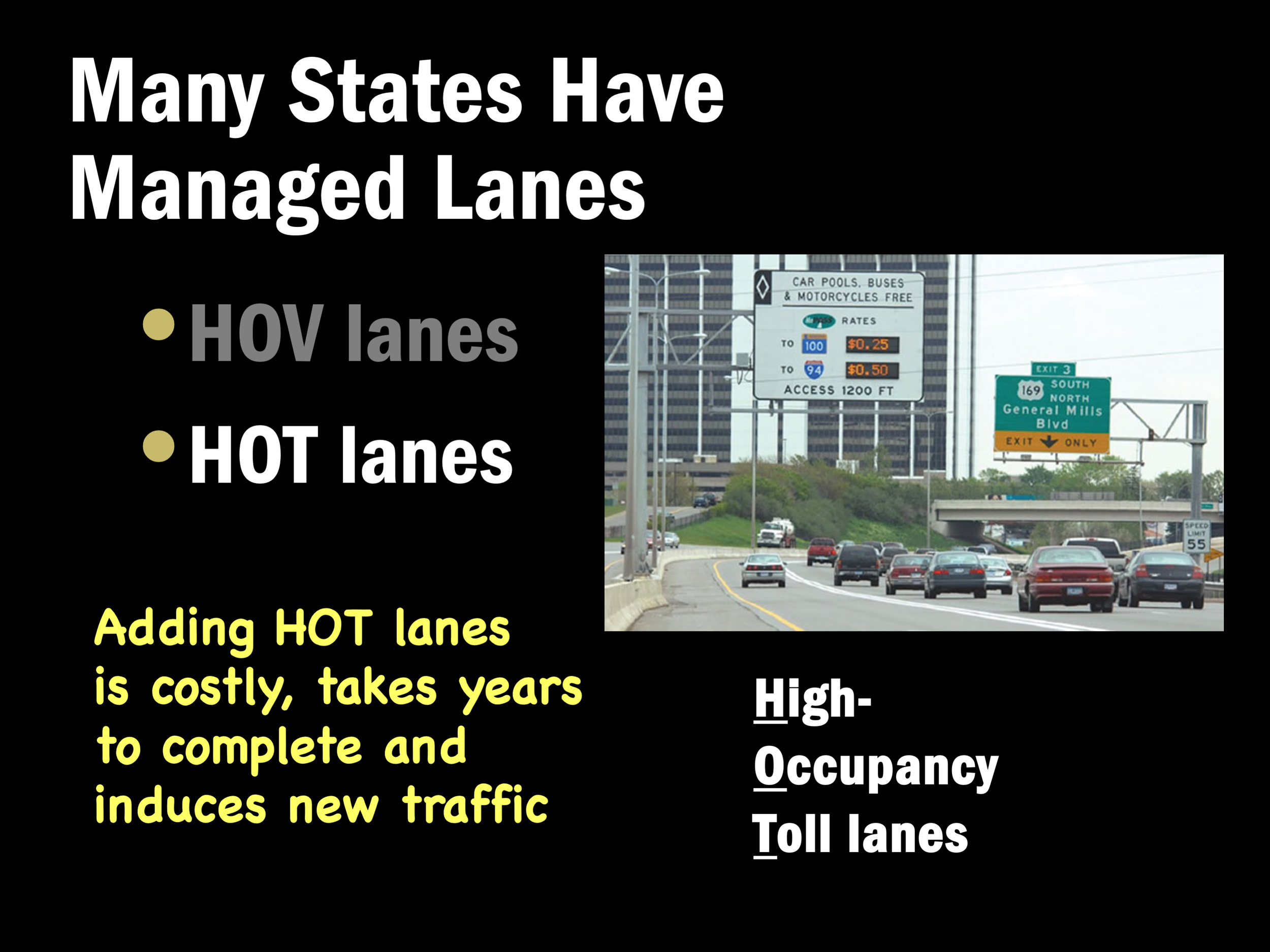

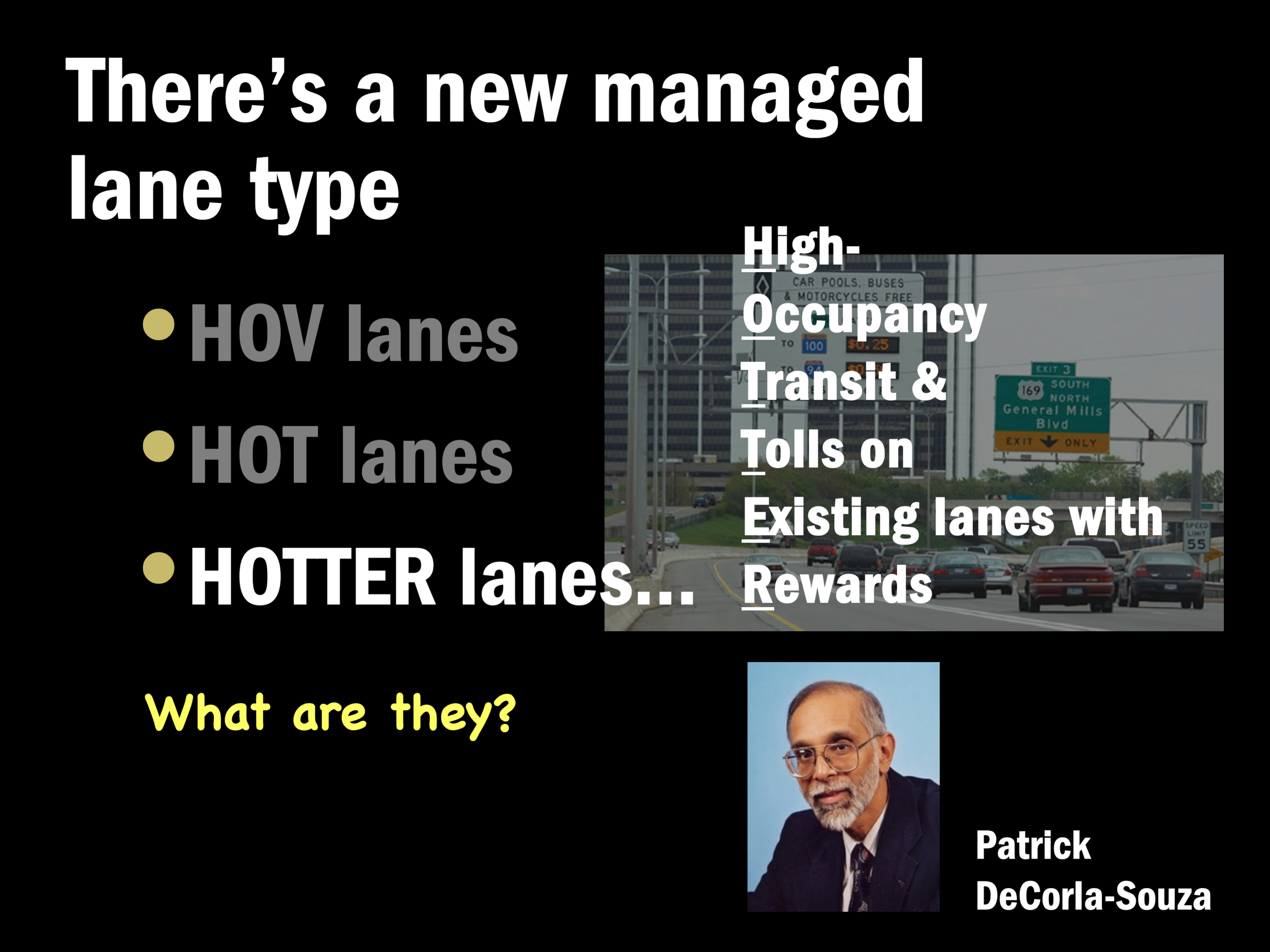

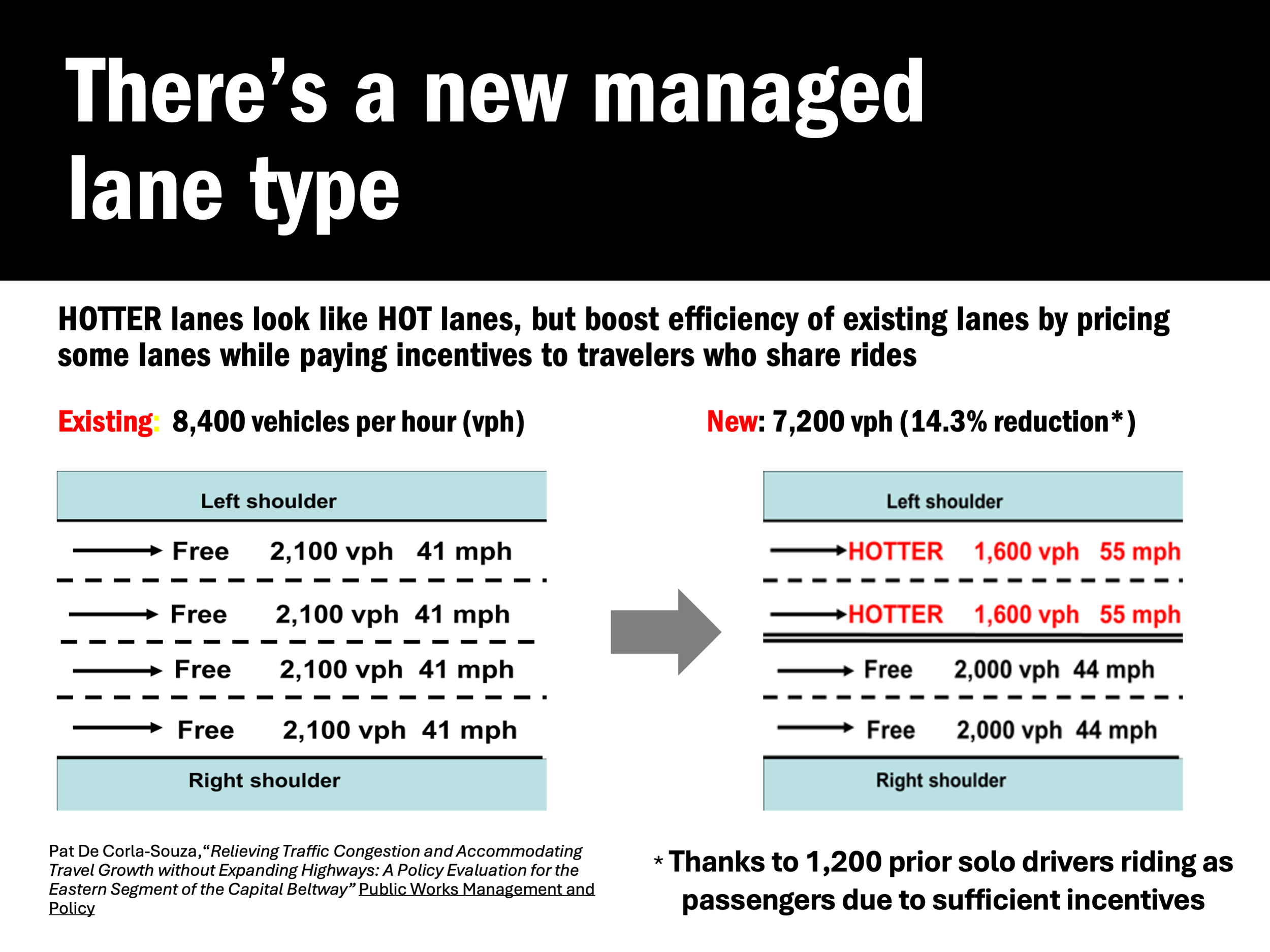

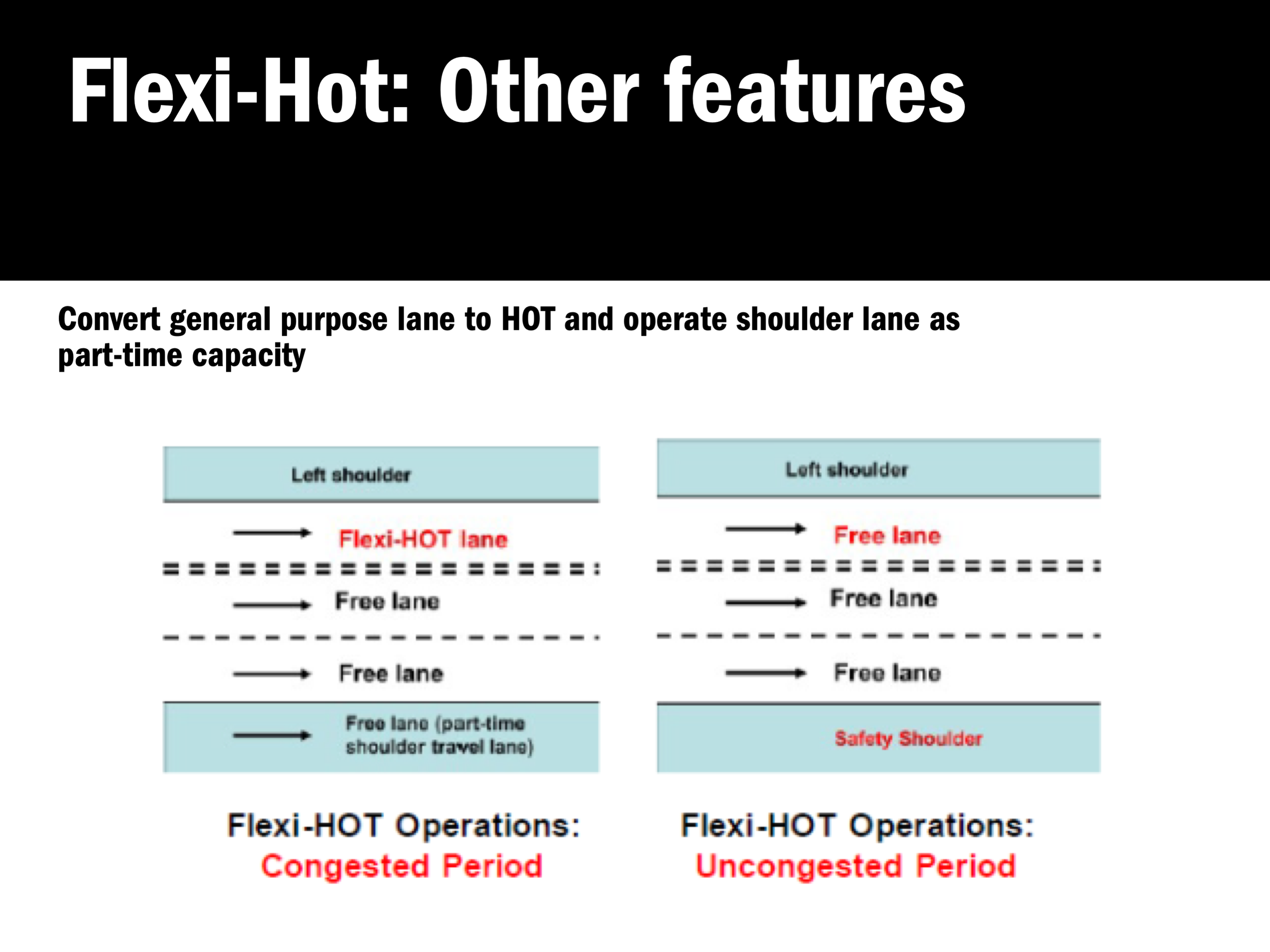

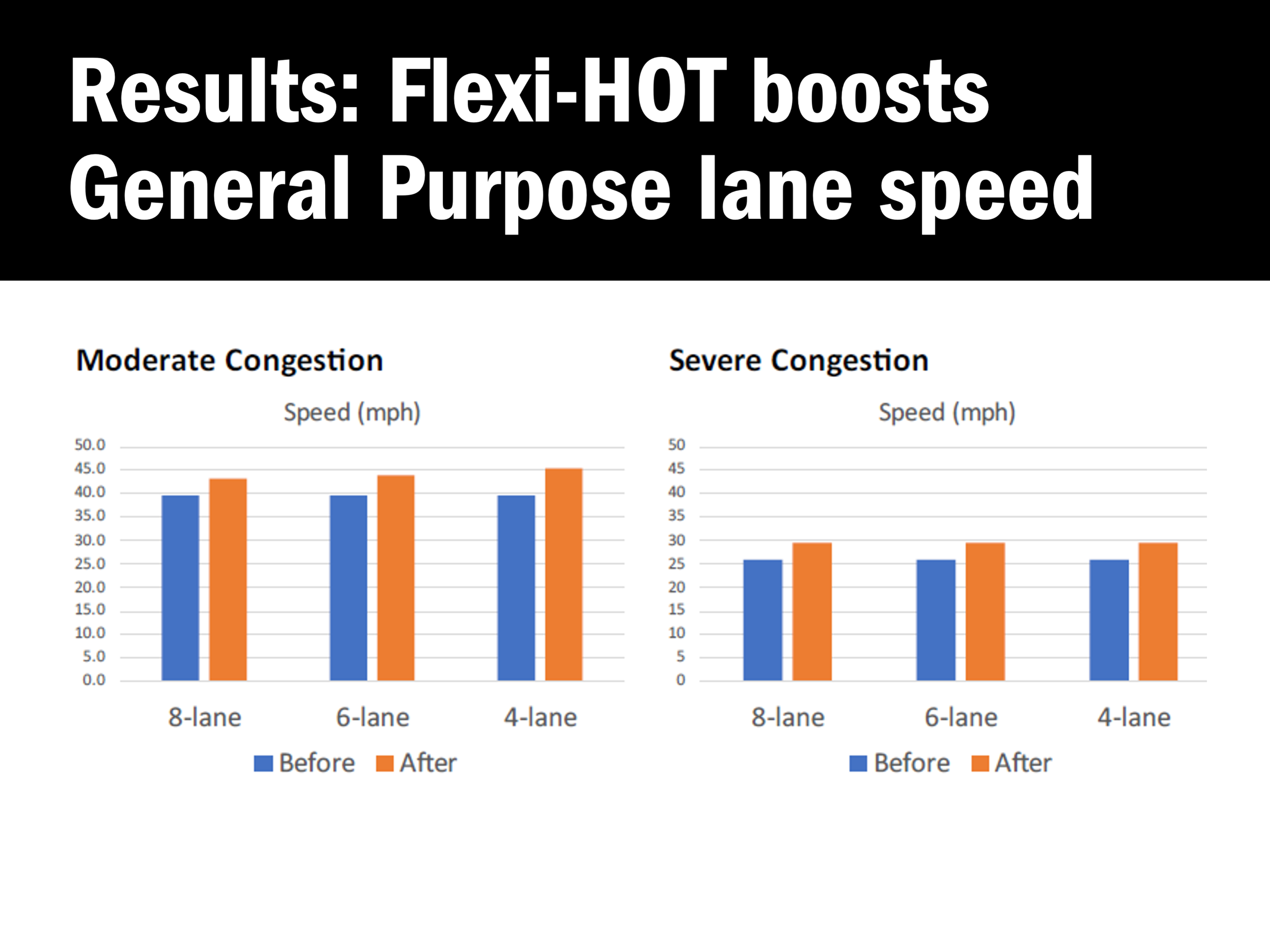

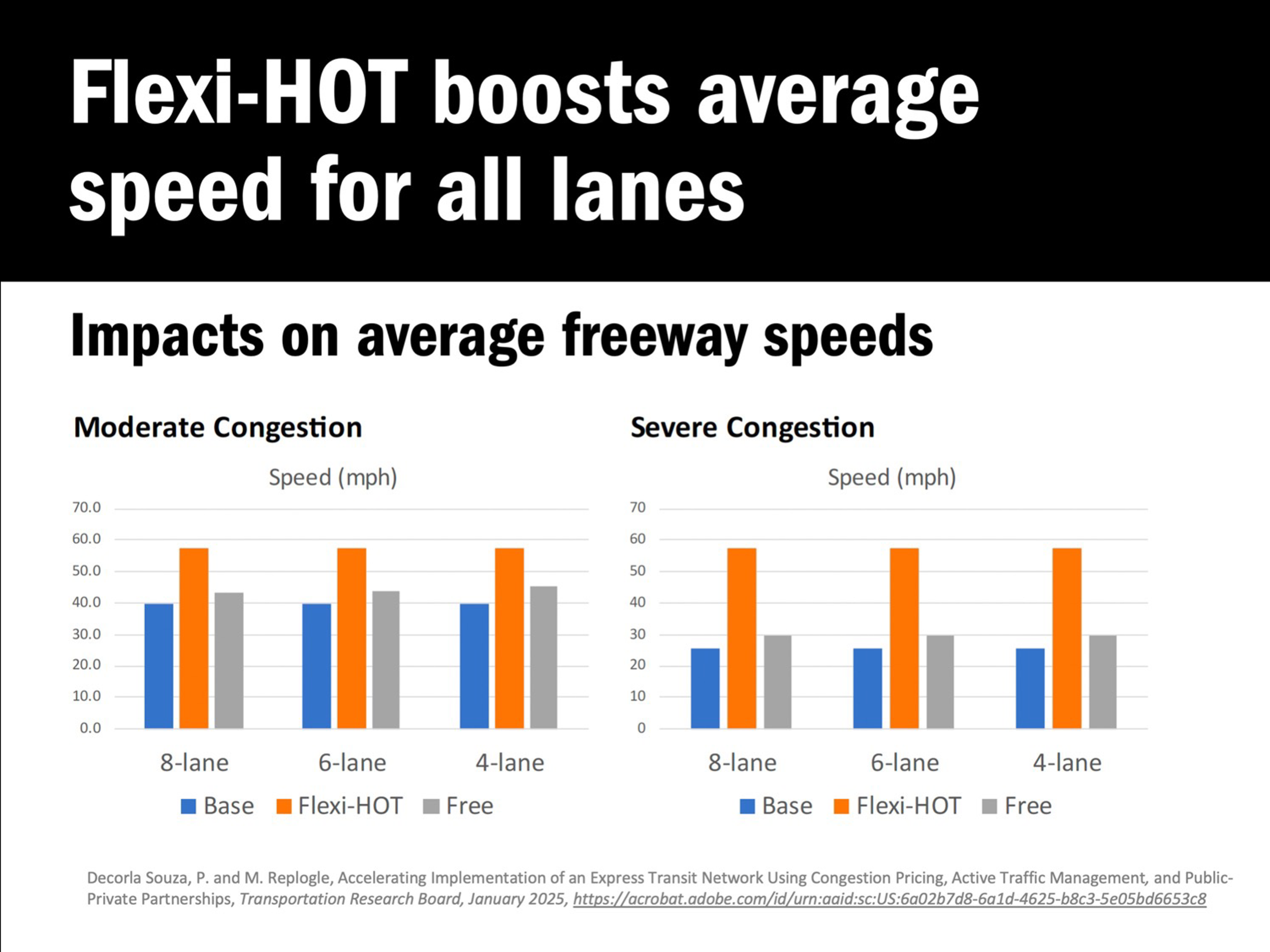

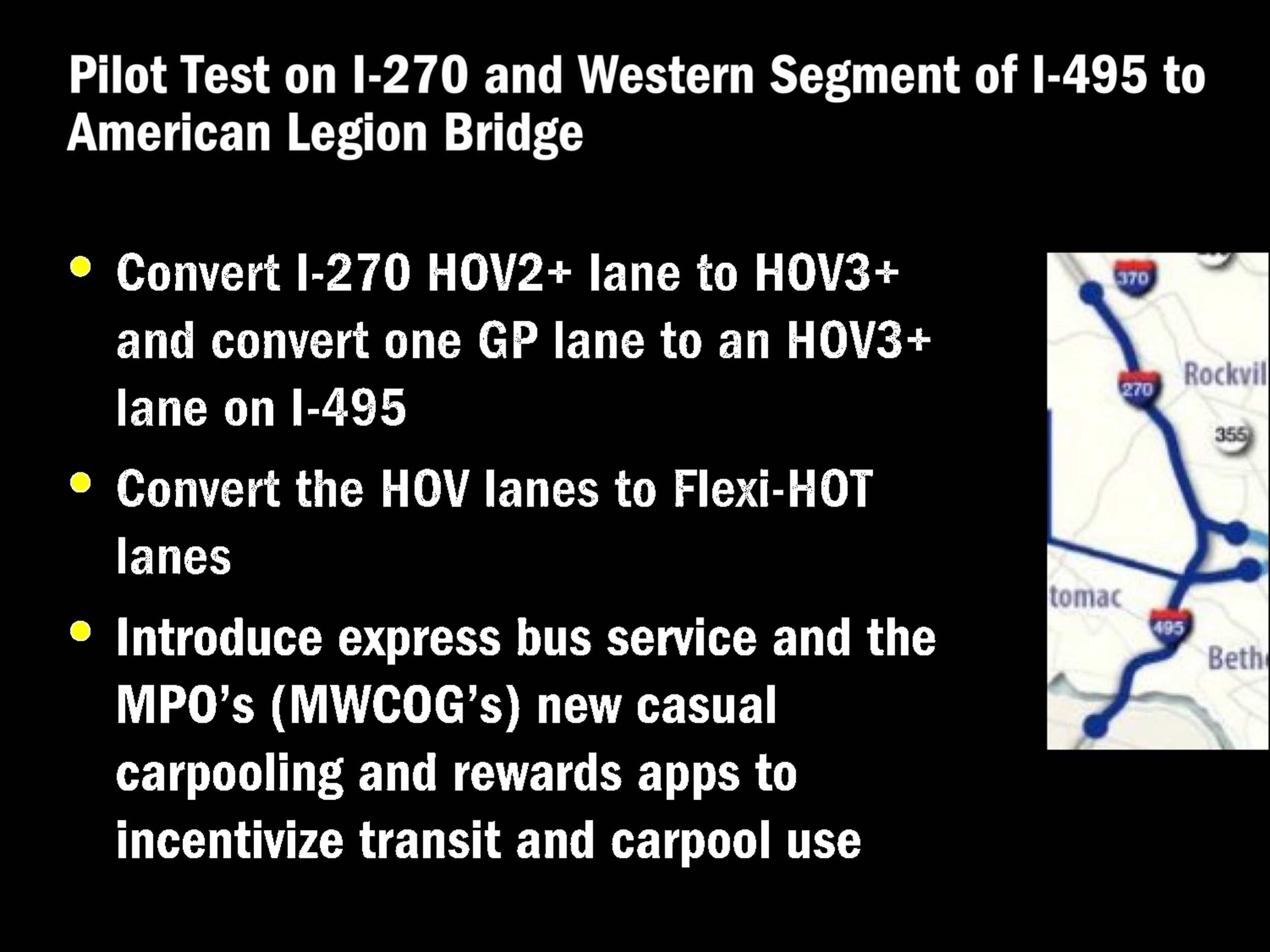

By the 1980s and 1990s, some U.S. transportation planners began recognizing this pattern. Rather than expanding freeways, they shifted focus to reducing demand through investment in transit, biking, walking and travel demand management (TDM) strategies. But in many regions, especially where political pressure favored sprawl, the "build baby build" approach persisted. As federal funding waned, state and local governments increasingly turned to public-private partnerships and toll roads to finance new highway capacity. Many of these projects included managed lanes—such as HOV or HOT lanes—as operational strategies to manage congestion and generate revenue.

While managed lanes can ease traffic temporarily, they don’t solve the underlying problem. HOT lanes (where solo drivers can pay to use carpool lanes) often require costly infrastructure like special ramps and lane separators. HOV lanes (reserved for carpools) may go underused because the carpool rules are hard for many drivers to meet. Even when these lanes succeed in reducing congestion during peak hours, the relief is usually short-lived. The root issue remains: adding road space—even if it’s tolled—makes driving feel cheaper or more convenient, which leads to more driving and more congestion.

Congestion pricing, as used in cities like Singapore, Stockholm, and now New York, offers a more effective approach. By charging vehicles to enter high-demand areas—often with pricing that varies by time or demand—these programs reduce traffic more equitably and affordably than building new lanes. However, they can face political resistance, especially in suburban regions where alternatives to driving remain limited.

Recognizing these challenges, Michael Replogle and a coalition of transportation leaders have introduced a new framework:

IC4M – Integrated Congestion and Multi-Modal Mobility Management

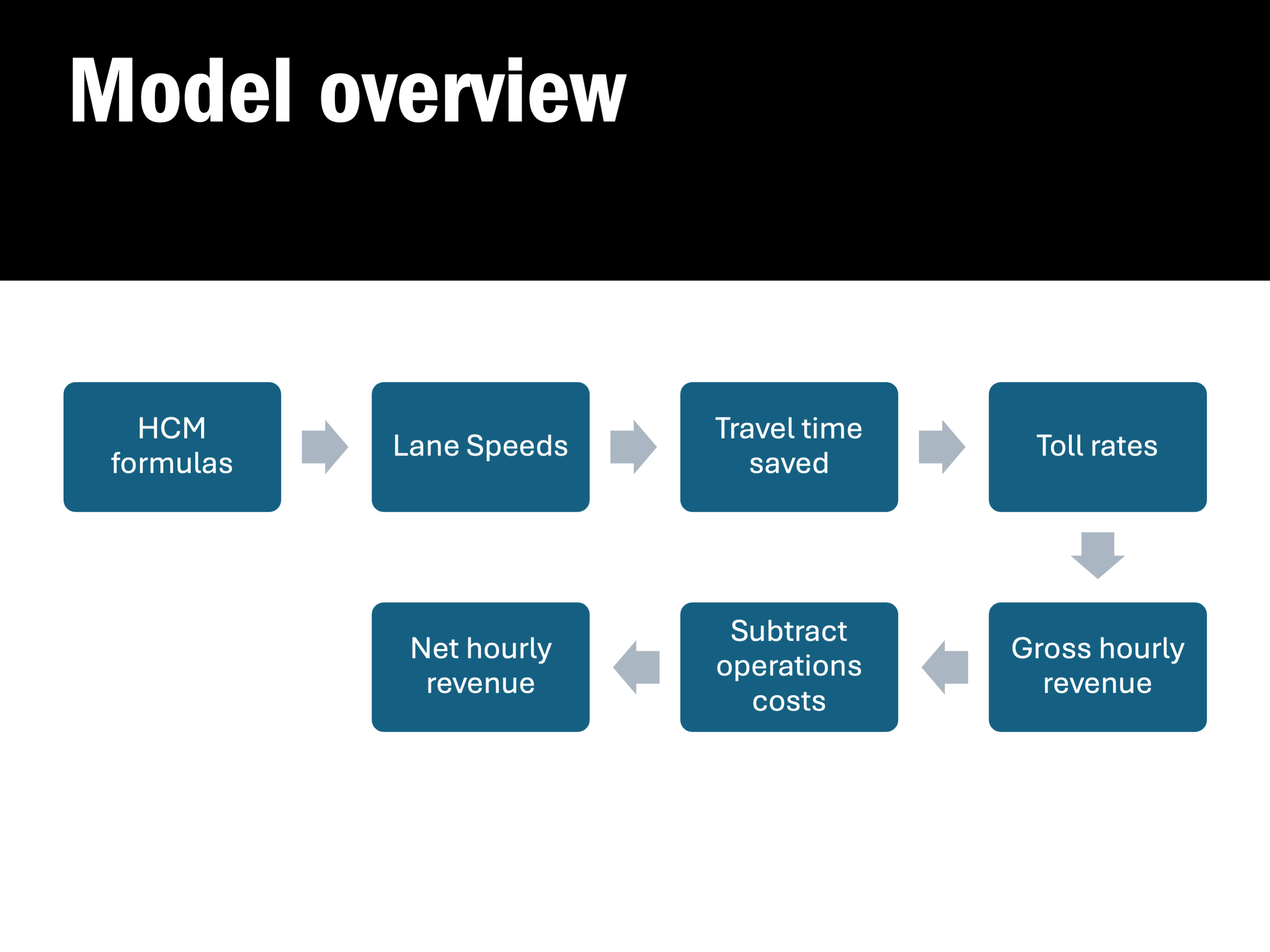

IC4M builds on lessons from past efforts but goes further. It envisions freeway corridors not just as car-only spaces, but as integrated mobility systems. Combining policy, engineering, TDM strategies and consumer incentives, IC4M aims to:

Repurpose existing freeway infrastructure with a complete-streets mindset

Add parallel or on-route transit options

Offer real-time, monetary incentives for carpooling, off-peak travel, transit use, and active modes

Use data-driven tools to manage demand dynamically and equitably

Rather than relying on a single solution, IC4M embraces a suite of coordinated interventions to make better use of the infrastructure we already have.

We invite you to learn more about IC4M by reviewing the mini-deck below and exploring the resources on this page.

Additional Resources:

An article from The Guardian about residents of the Lone Star state who are fed up with freeways; “‘It’s just more and more lanes’: the Texan revolt against giant new highways”

A great video from Vox explaining induced demand using the example of Houston’s Katy Freeway; “How Highways Make Traffic Worse”

A companion article to the Vox video, above, by David Zipper; “Do bigger highways actually help reduce traffic?”

From Caltrans, a helpful infographic: Bigger Roads, More Lanes It shows how induced demand overwhelms efforts to build our way out of congestion

Another video explaining induced demand from the acclaimed Not Just Bikes series by Jason Slaughter; “More Lanes are (Still) a Bad Thing”

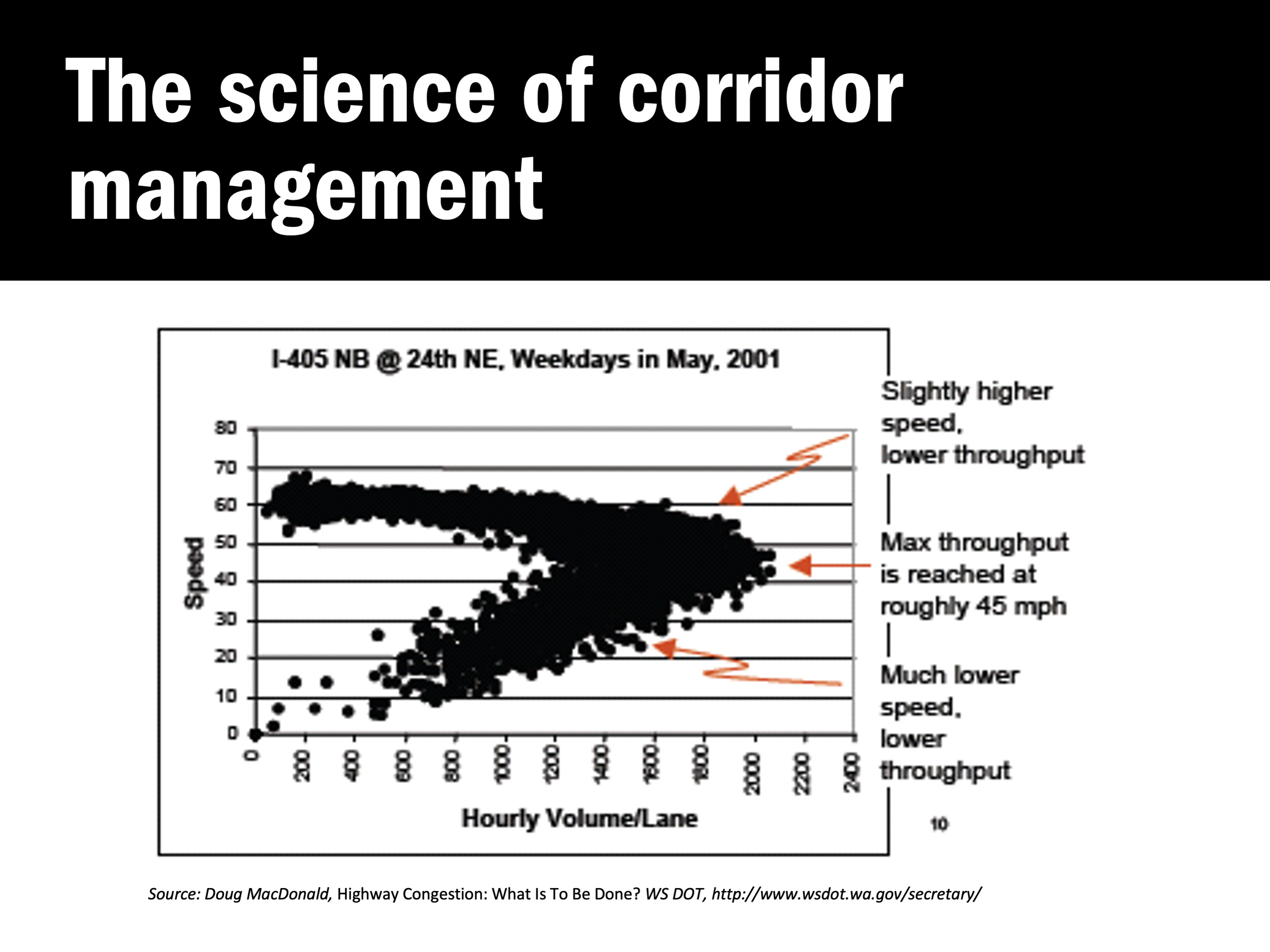

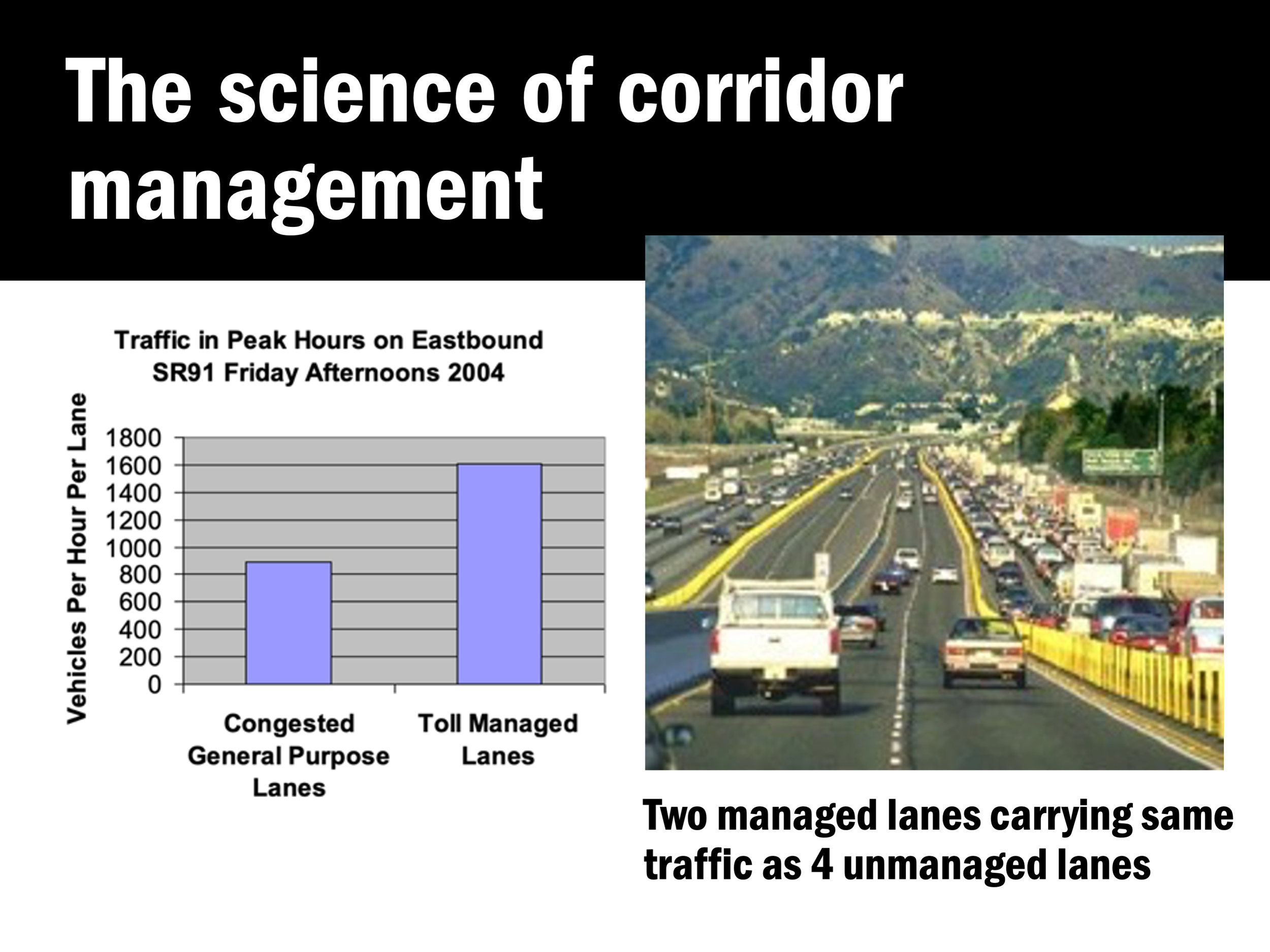

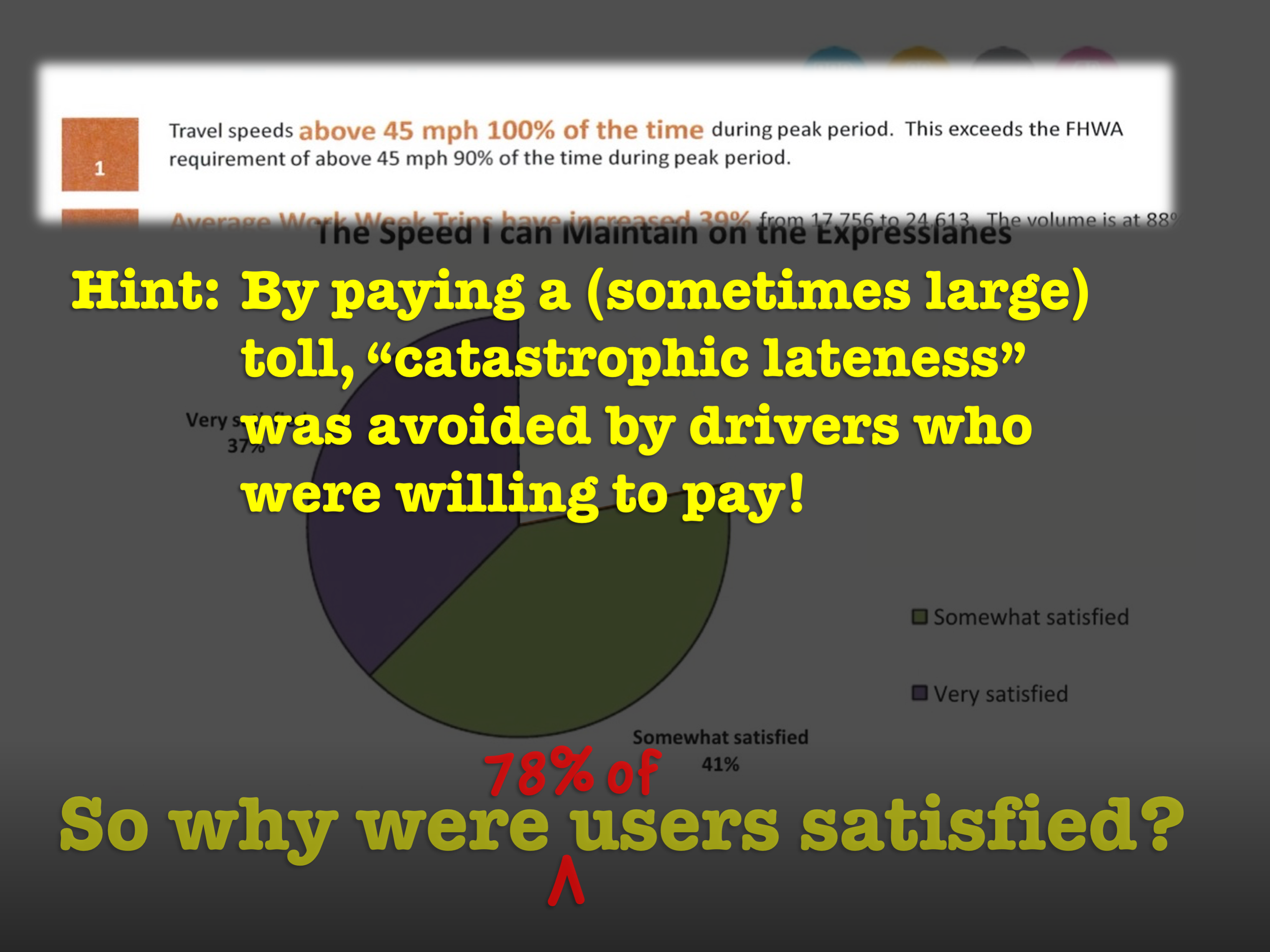

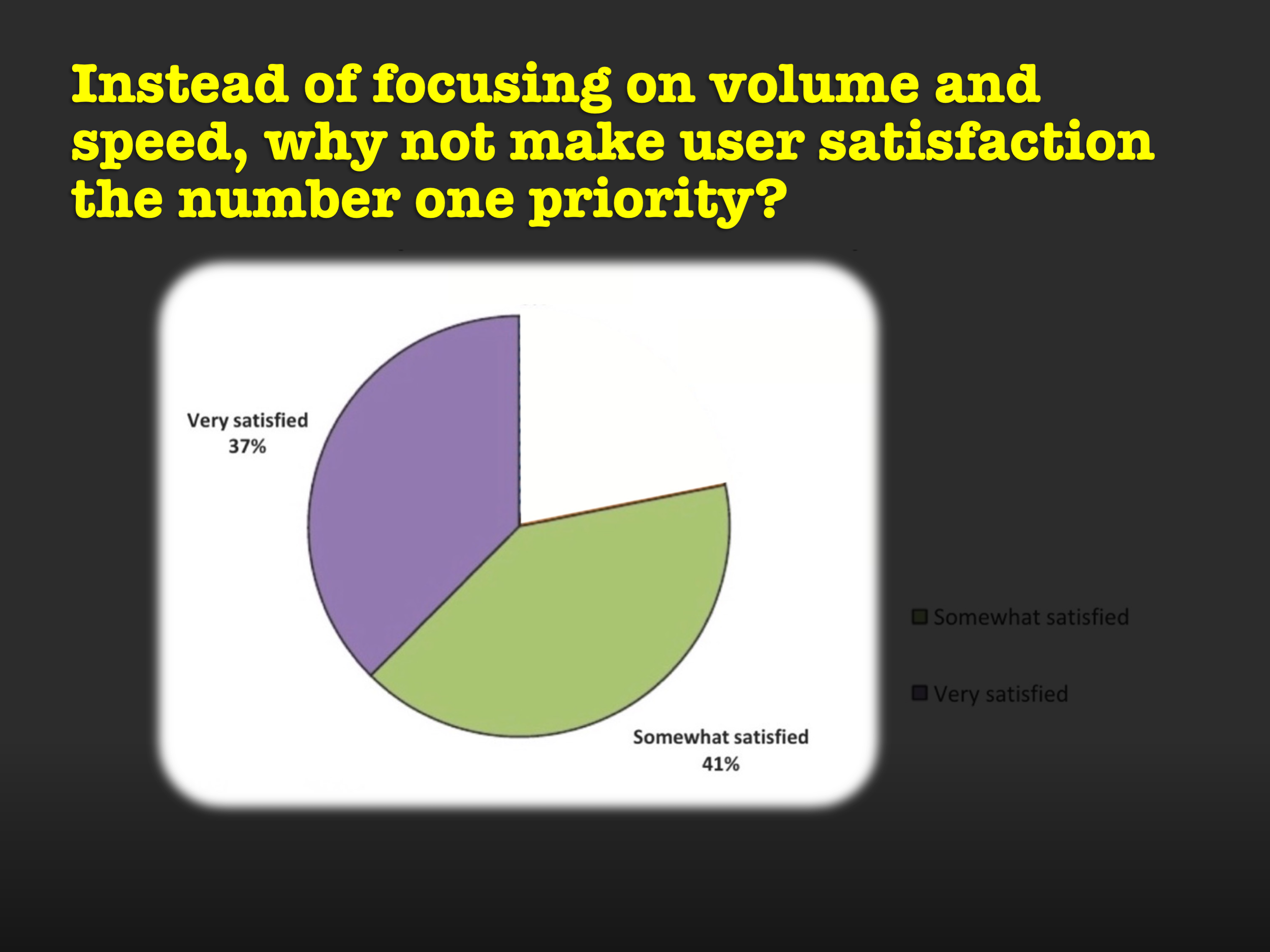

An empirical demonstration of the effectiveness of managed lanes; “The Doug MacDonald Challenge - Rice and Traffic Congestion”

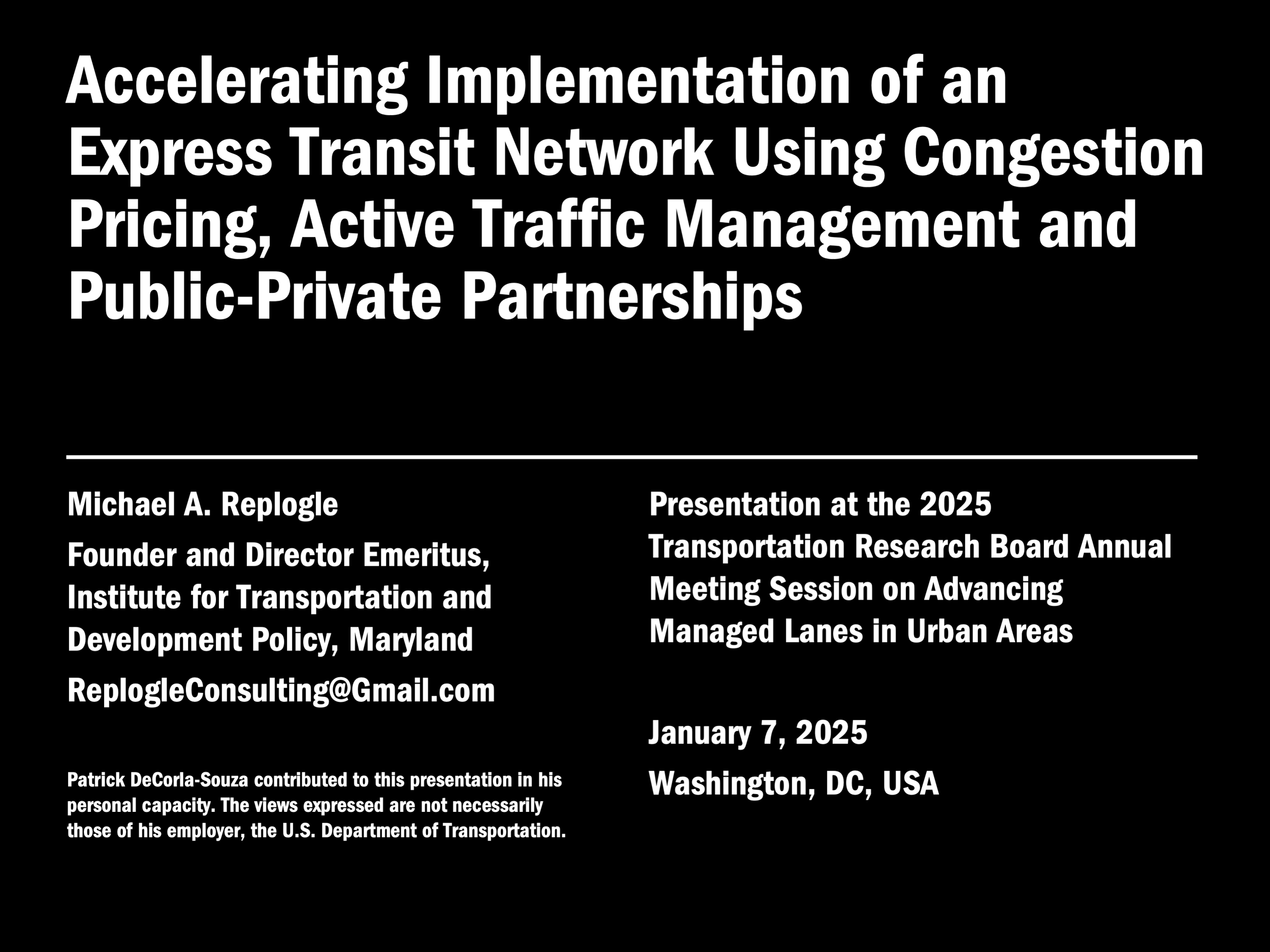

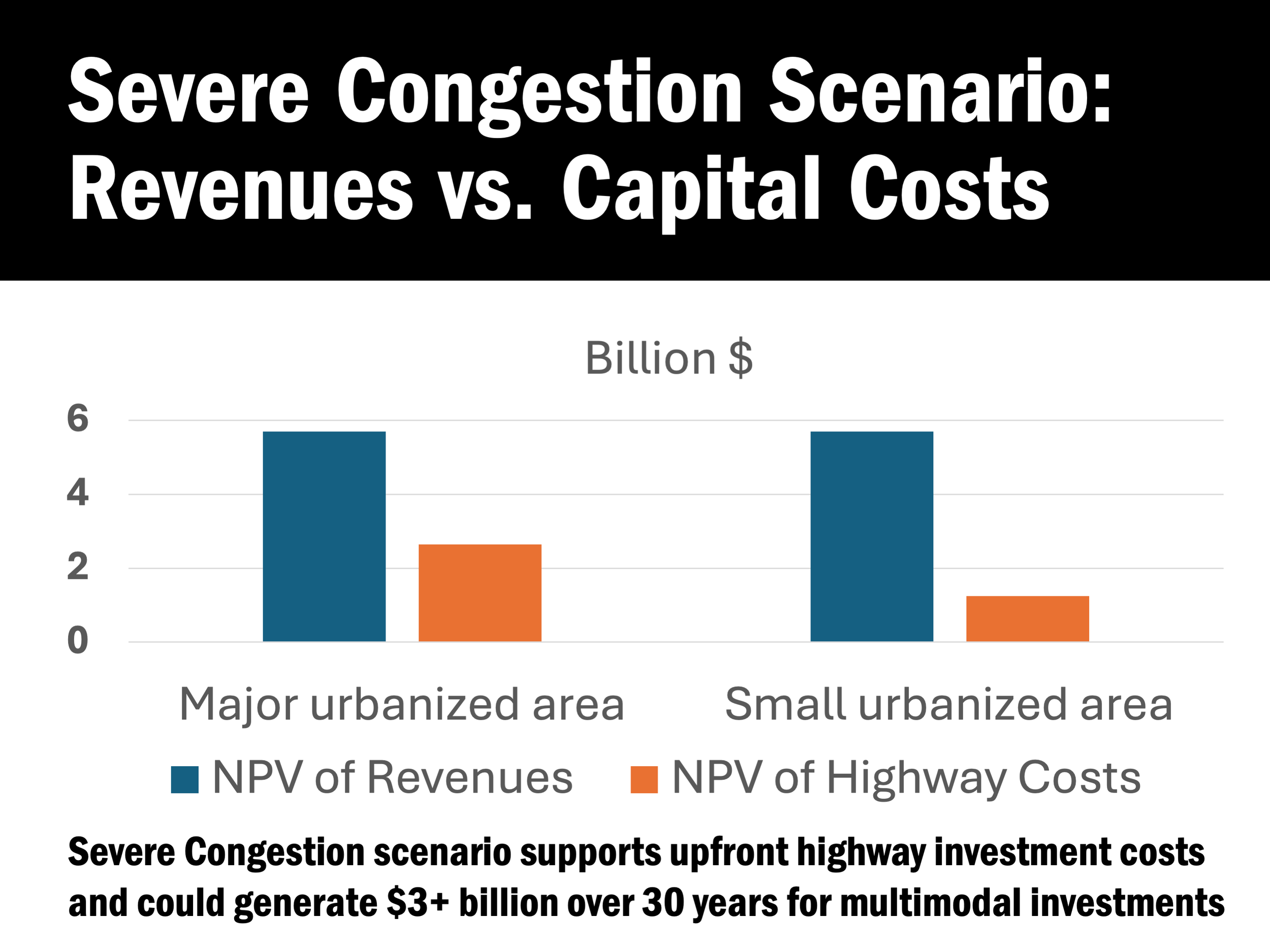

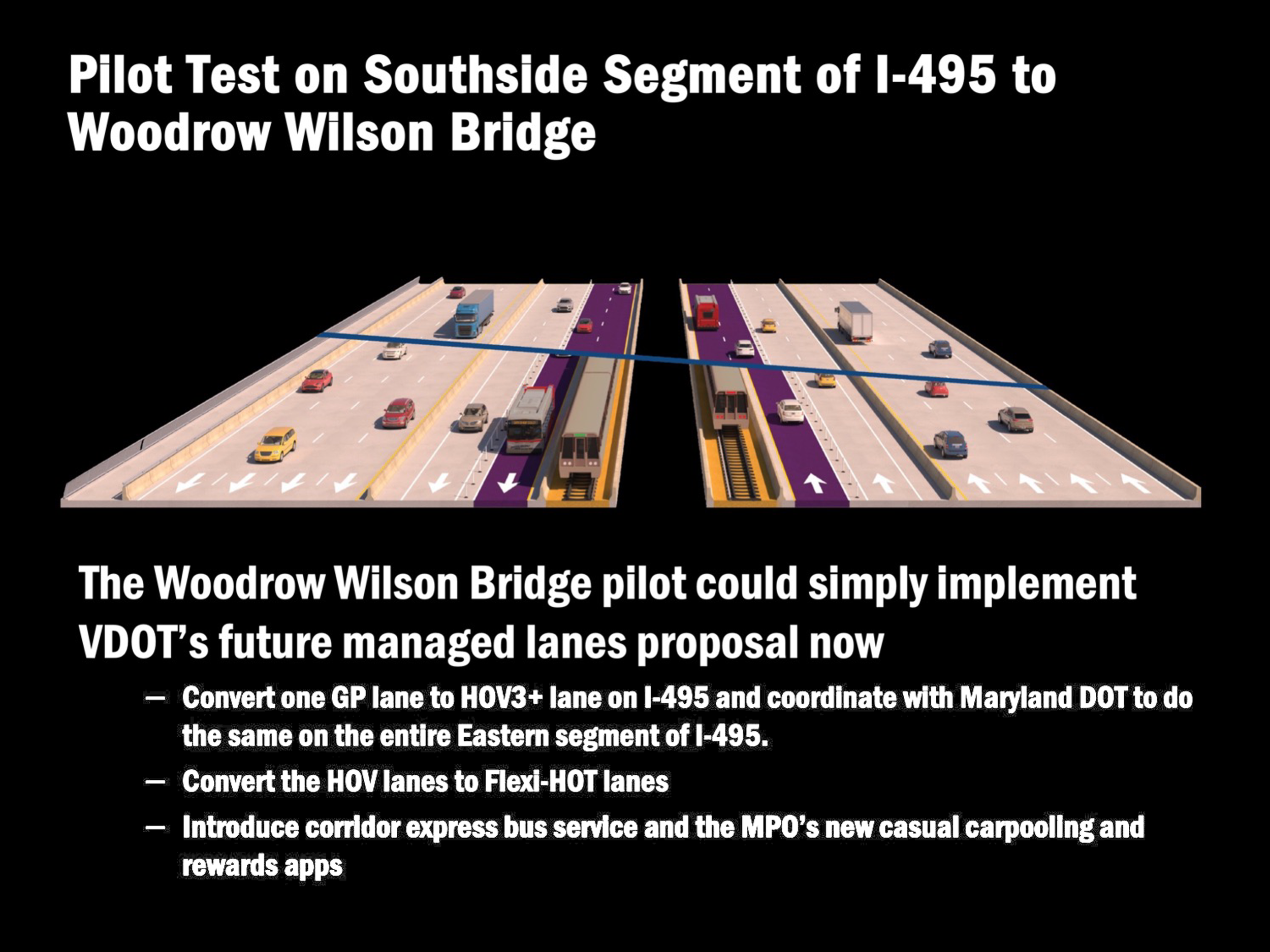

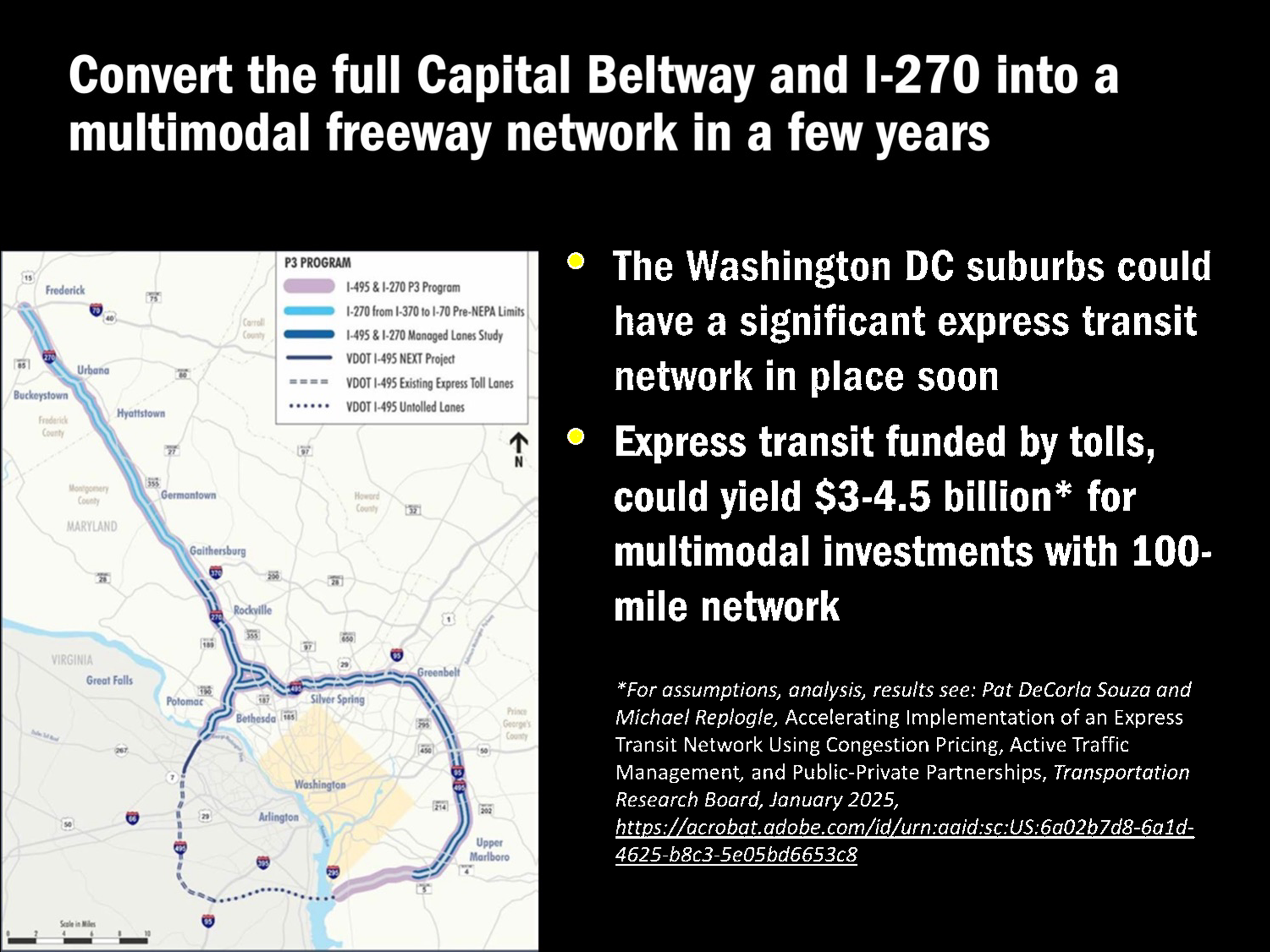

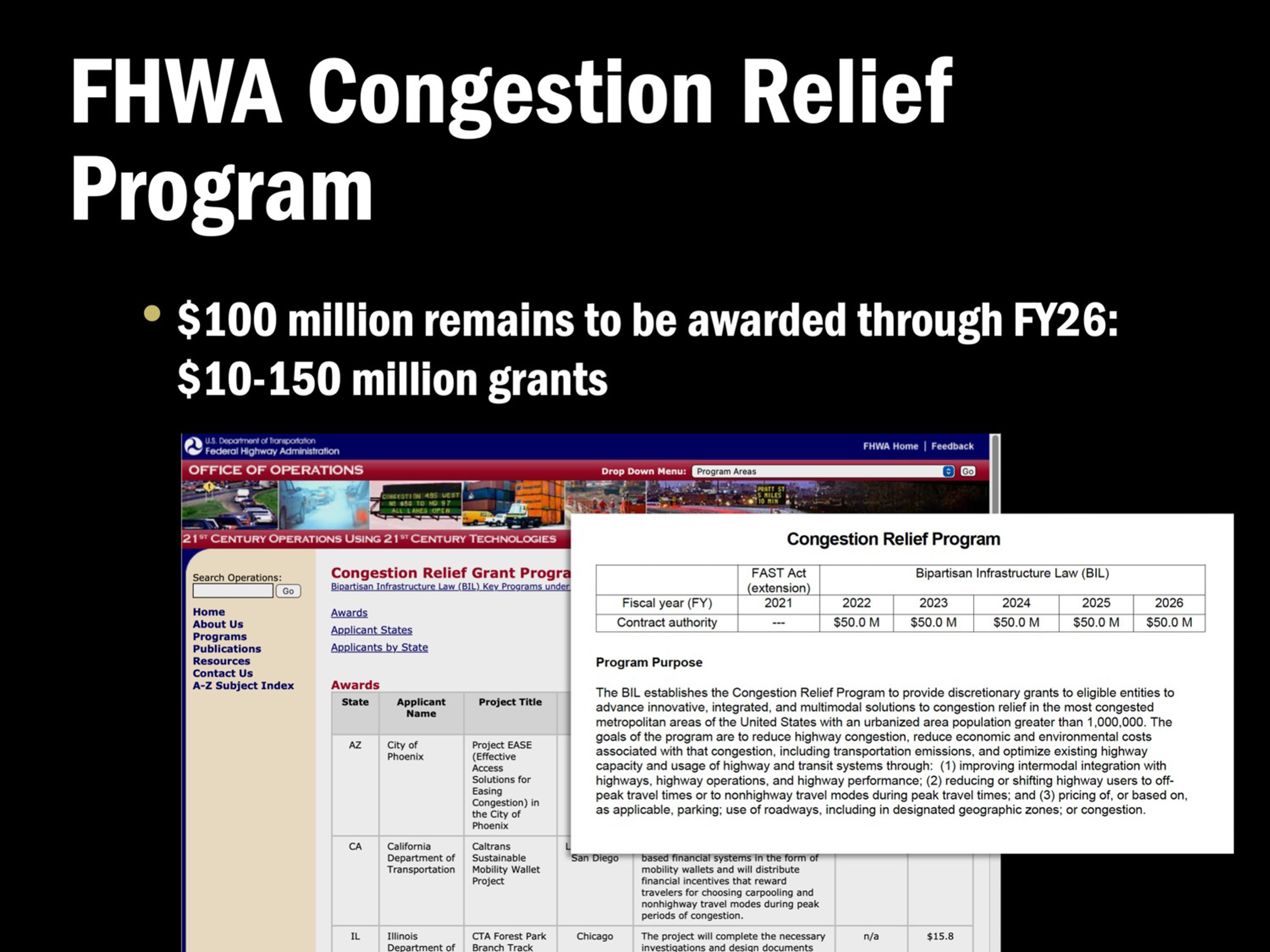

Michael Replogle’s 2025 presentation to the Transportation Research Board; Accelerating Implementation of an Express Transit Network Using Congestion Pricing, Active Traffic Management and Public-Private Partnerships (PDF of deck downloadable from link above; slideshow is below)

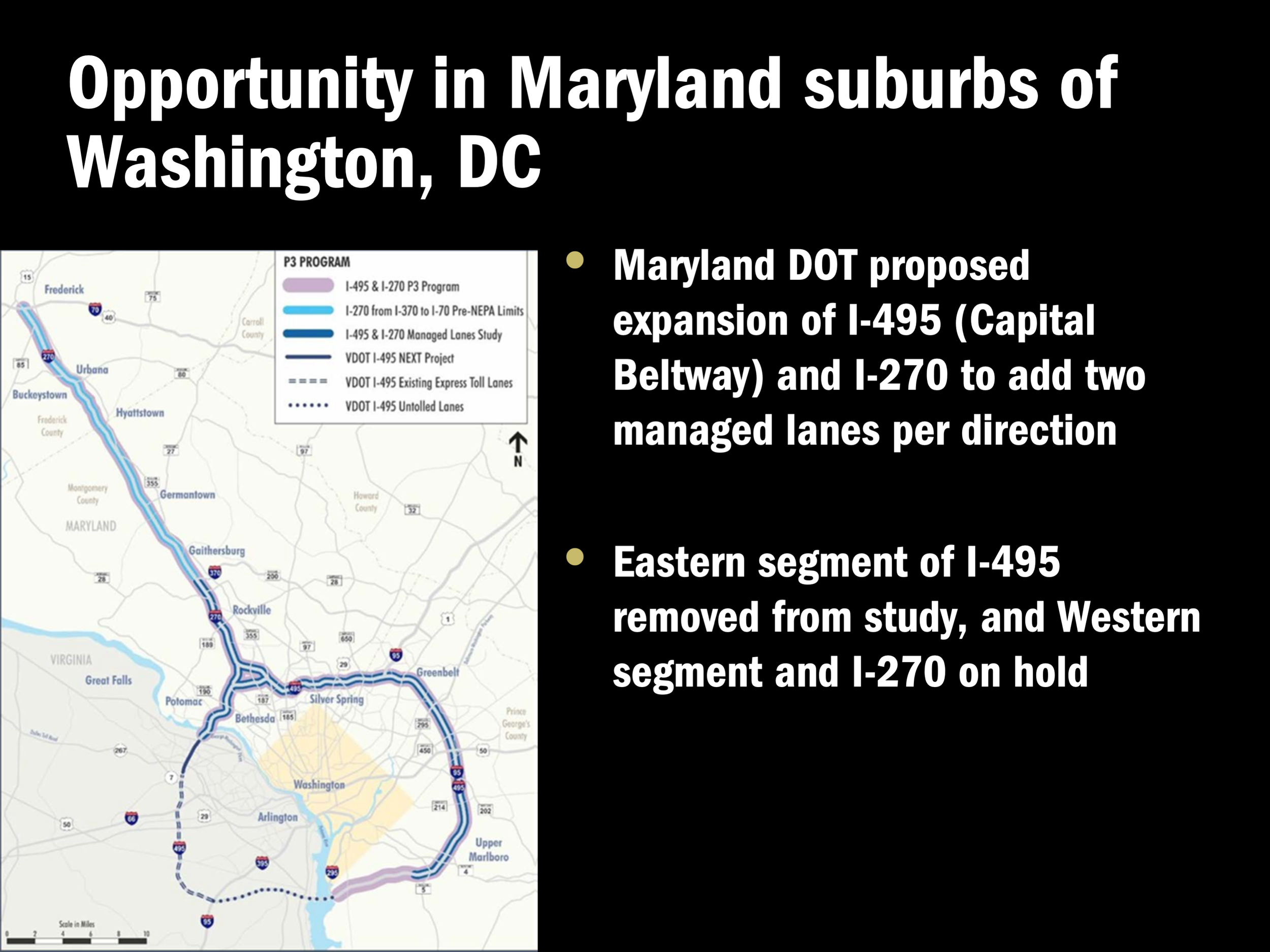

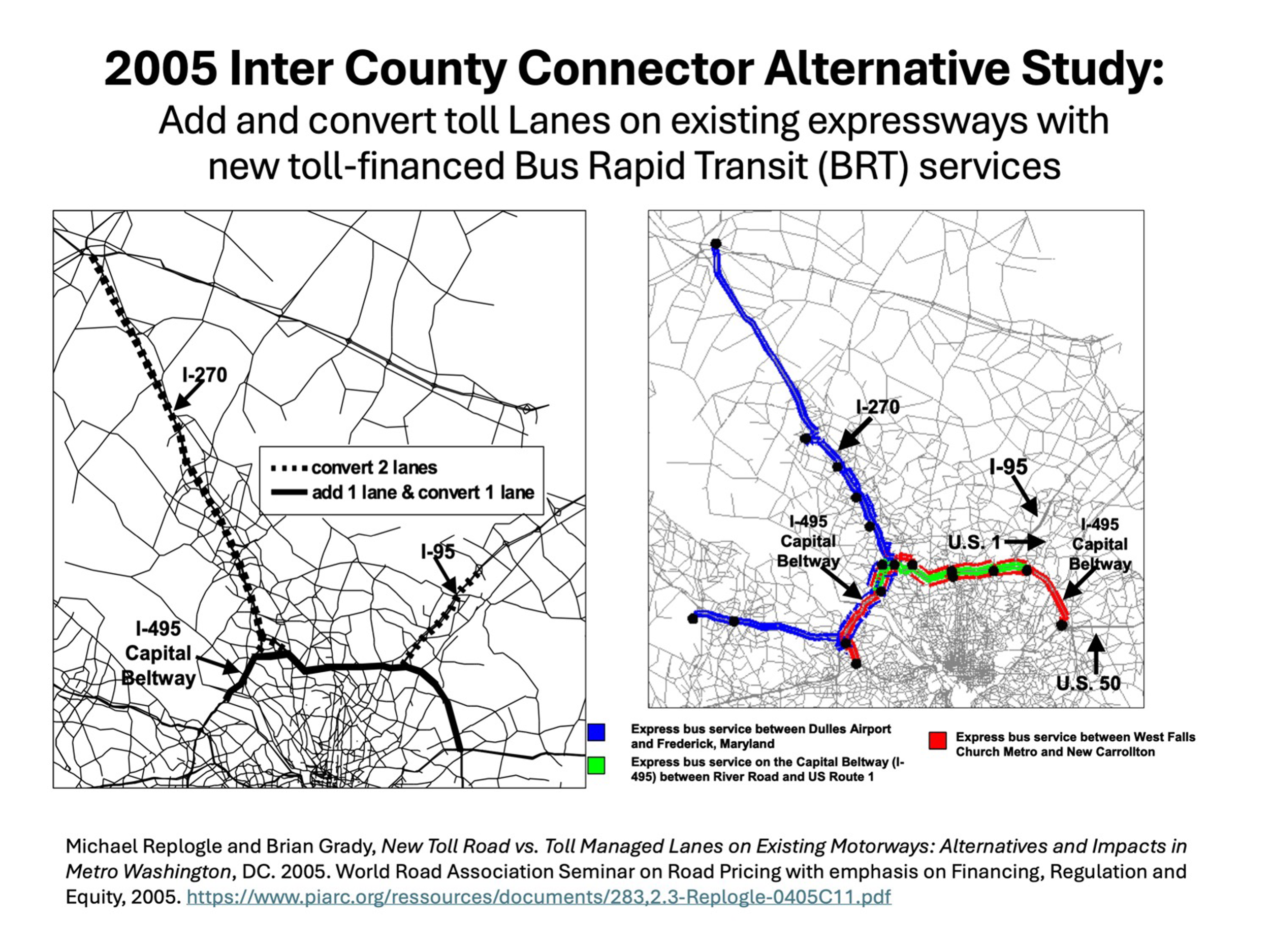

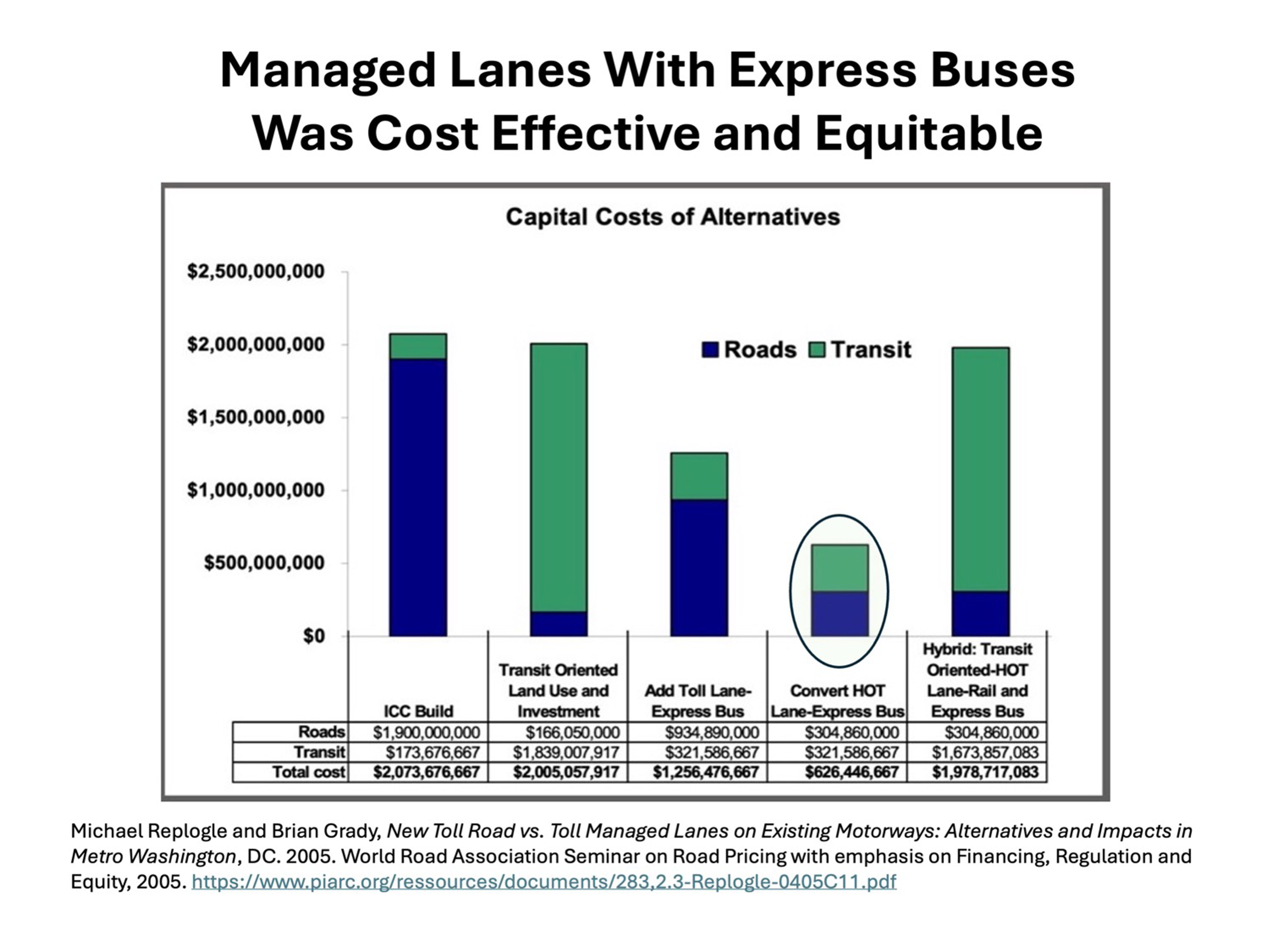

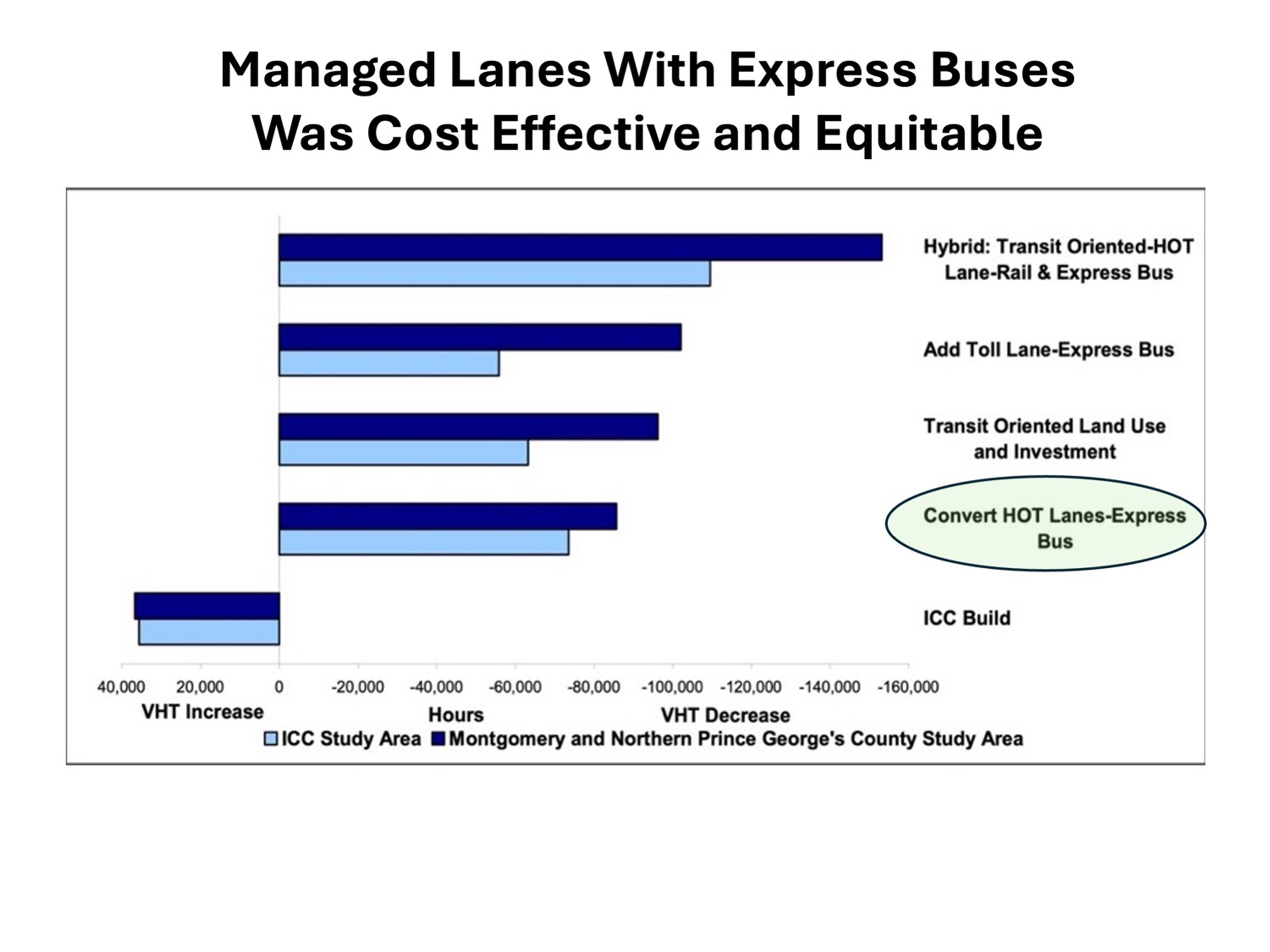

Michael Replogle’s narrated presentation on IC4M/Hotter Lanes; The IC4M Plan for Fixing Maryland’s Part of the DC Region’s Congestion (January, 2024; begins at 24:40) as an alternative to the possible expansion of I-495 and I-270 in the Maryland suburbs of Washington, DC

From Dissent magazine, a thorough debunking of road modeling, the pseudoscience used to justify the expansion of freeway corridors across the US; “Highway Robbery”

SmartGO’s NexTDM program summarized; This behavioral program is a key component of the IC4M program.

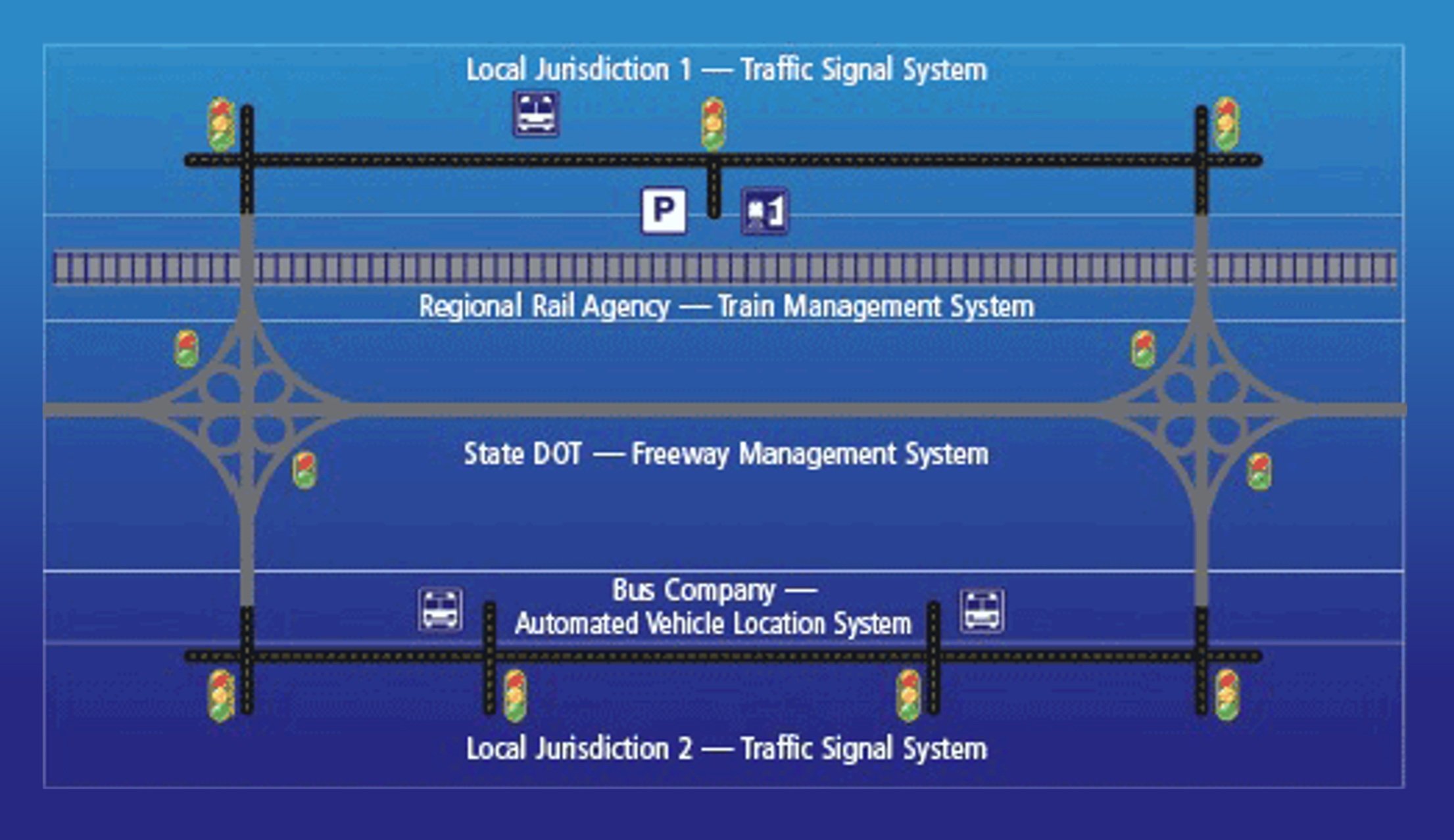

Integrated Corridor Management (ICM), an initiative of USDOT started in 2006, sought “to improve the movement of people and goods along metropolitan corridors through a multimodal, integrated transportation management approach.” Over time, the program helped to relieve episodic congestion from crisis events (such as an overturned truck blocking all lanes) but did little to reduce everyday traffic. An article from the March/April 2008 issue of Public Roads explains the concept.

Image courtesy of USDOT / Public Roads Magazine

Next Gen Policy’s report makes a strong statement about the need to limit VMT (vehicle miles traveled) growth; “California at a Crossroads - Unleashing Climate Progress in Transportation Planning.”

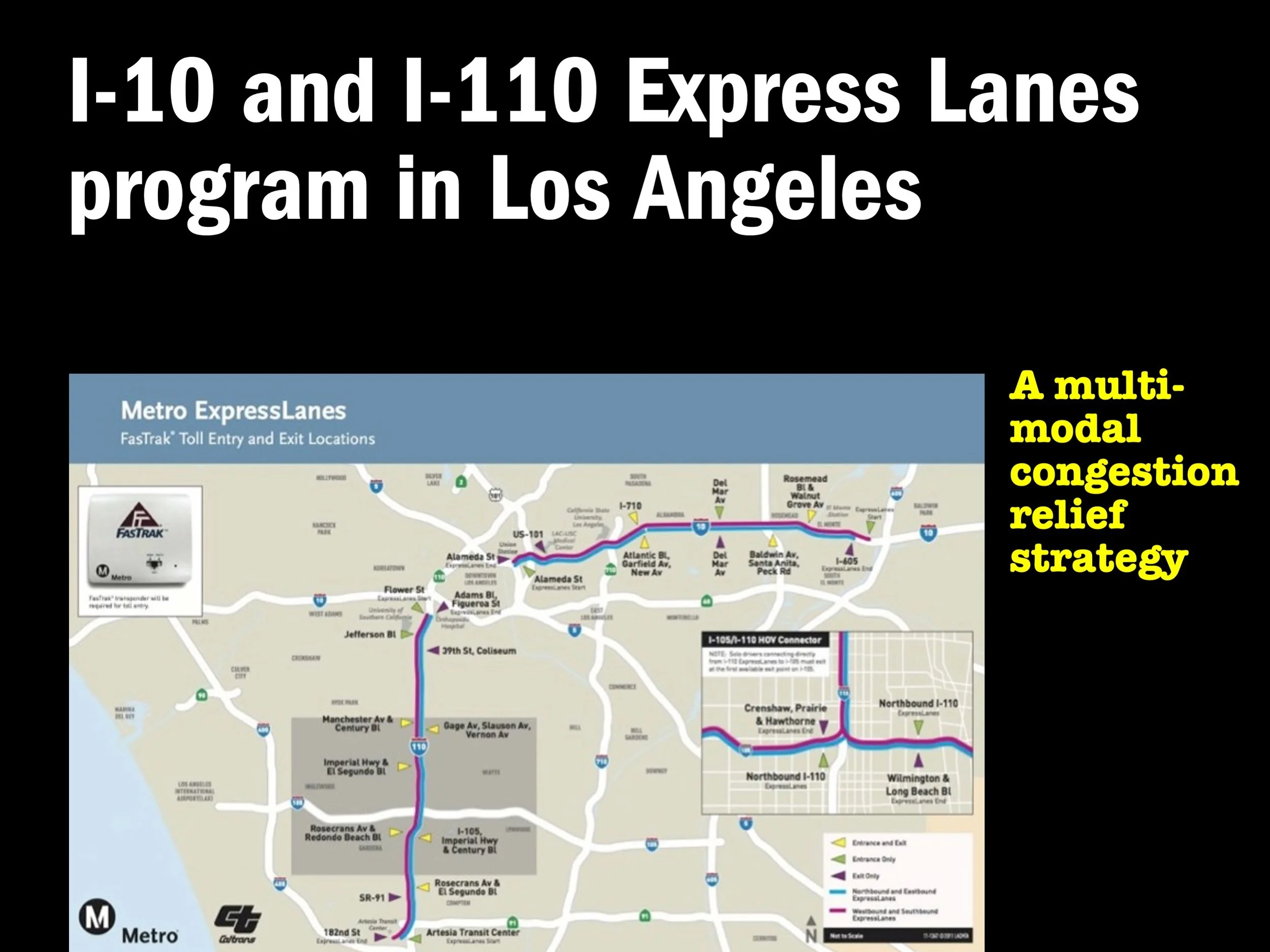

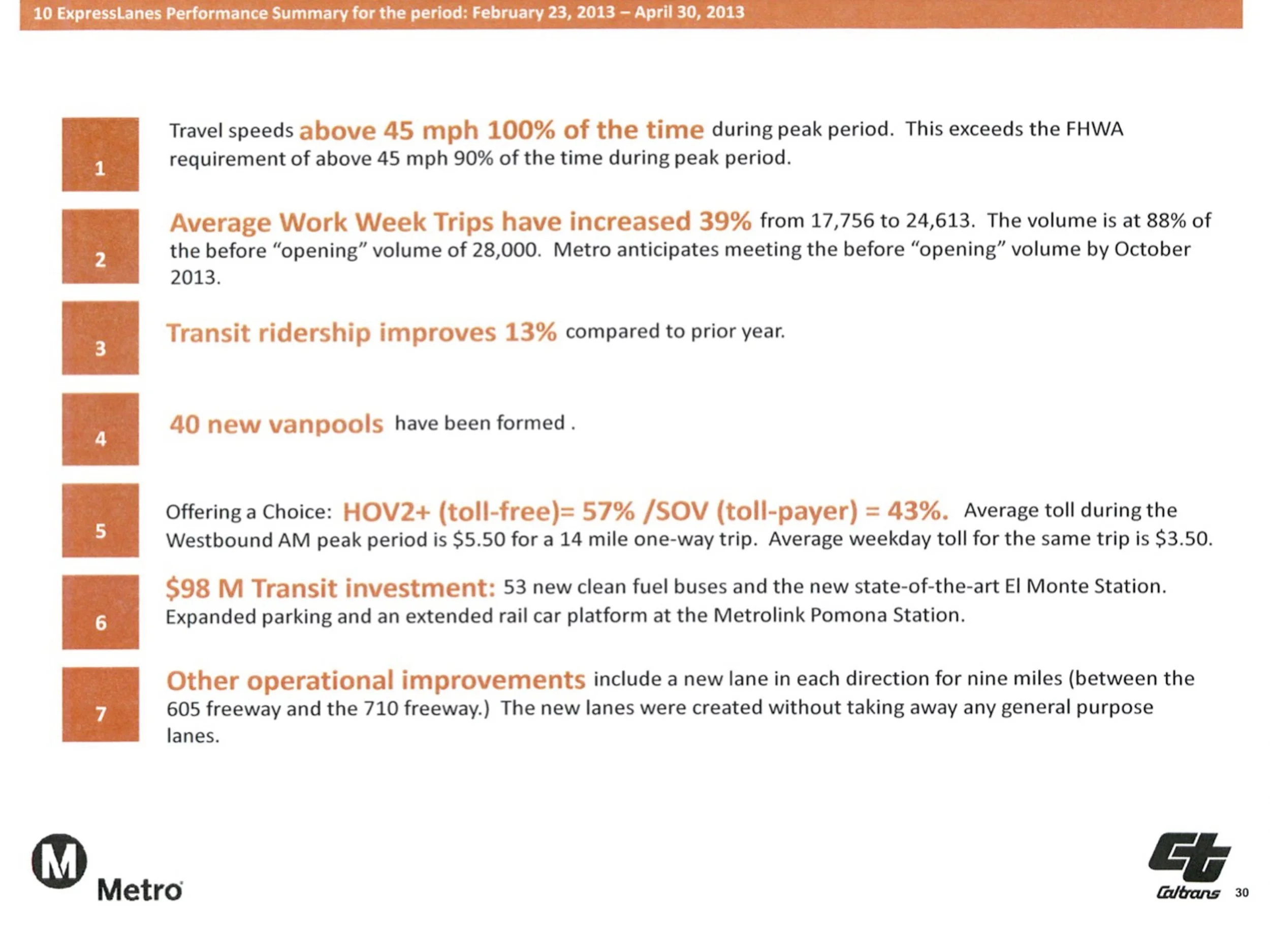

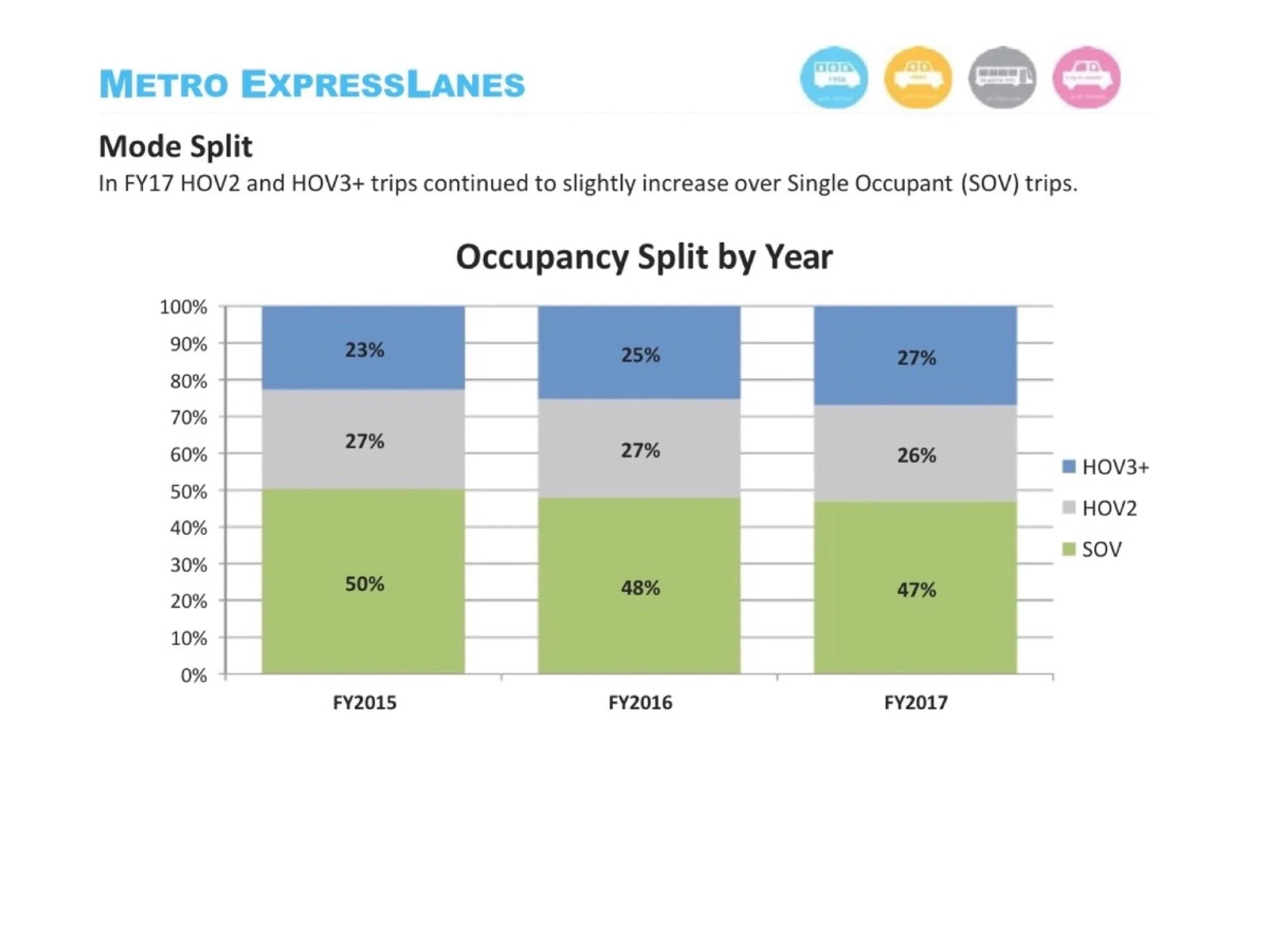

Precedent employing some features of IC4M: